I first heard the term "land acknowledgement" at a November 2020 seminar called The Role of ADR in Disputes Involving Gender-Based Violence, hosted by the Ohio State Journal on Dispute Resolution. (I learned other new language at that event, too.)

I heard the term again in Northwestern University's first event in its Dream Week series of virtual events leading up to Dr. Martin Luther King's Day.

Mariame Kaba presented the keynote for the first event. But before she spoke, Chantay Moore presented a land acknowledgement. Ms. Moore is a member of the Navajo Nation, and is also of African-American heritage.

What is land acknowledgement?

From Northwestern University's land acknowledgement page, I've gleaned this definition:

"A Land Acknowledgement is a formal statement that recognizes and respects Indigenous Peoples as traditional stewards of this land and the enduring relationship that exists between Indigenous Peoples and their traditional territories. ....

.... [A land acknowledgement] is an expression of gratitude and appreciation to those whose territory you reside on, and a way of honoring the Indigenous people who have been living and working on the land from time immemorial. It is important to understand the long standing history that has brought you to reside on the land, and to seek to understand your place within that history. Land acknowledgements do not exist in a past tense, or historical context: colonialism is a current ongoing process [emphasis added], and we need to build our mindfulness of our present participation."

The Native Governance Center offers a rich, reader-friendly, practical guide here for presenting a meaningful land acknowledgement. Another good explanation is at Native Land Digital here.

Michael Redhead Champagne, author of North End MC, shares an interview he conducted in 2015 with Native Land Digital founder, Victor Temprano, about why it's important for all of us, "settlers" in particular, to educate ourselves about indigenous peoples who live(d) where we live:

MC: Why is it important for non-indigenous people to involve themselves as respectful allies in the indigenous struggle in 2015 Canada?

Victor: It’s important for settlers to engage with Indigenous history and nations on many levels – spiritual, physical, emotional, and more. It’s not to ‘help’ Indigenous people or cultures (at least not in the traditional sense of ‘charity’), but to help settlers get educated, to grow and to begin the hard process of decolonization. I don’t know what decolonization really looks like or feels like in our settler society, but I know it needs to happen, whether for moral, environmental, spiritual, legal, or historical reasons (or more). It is a inter-generational struggle to decolonize, and it’s already been going on, and now is a good time as any to find a way to engage one’s skills in a meaningful way.

The Association of Public & Land-Grant Universities offers a piss-poor, self-serving, so-called land acknowledgement here.

Before removal, enslavement, or extermination, what indigenous families and communities lived - and live - in what are now called Birmingham and Alabama?

Here is an interactive map that shows us which indigenous peoples lived (live) in Birmingham and Alabama (and throughout the world).

From Encyclopedia of Alabama:

Alabama's indigenous history can be traced back more than 10,000 years, to the Paleoindian Period. Cultural and technological developments brought changes to the societies that inhabited what is now Alabama, with the most visible evidence of those changes being the remarkable earthen mounds built by the Mississippian people throughout the Southeast, in Alabama most notably at Moundville. By the time European fortune hunters and colonialist explorers arrived in the sixteenth century, the Indian groups in the Southeast had coalesced into the cultural groups known from the historic period: the Cherokees, Choctaws, Creeks, and Chickasaws, and smaller groups such as the Alabama-Coushattas and the Yuchis. As more Europeans and then U.S. settlers flooded into the Southeast, these peoples were subjected to continual assaults on their land, warfare, the spread of non-native diseases, and exploitation of their resources. In the 1830s, the majority of the Native Americans in Alabama were forced from their land to make way for cotton plantations and European American expansion. Today, the MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians and the Poarch Band of Creek Indians maintain their traditions on portions of their tribal homelands in the state.

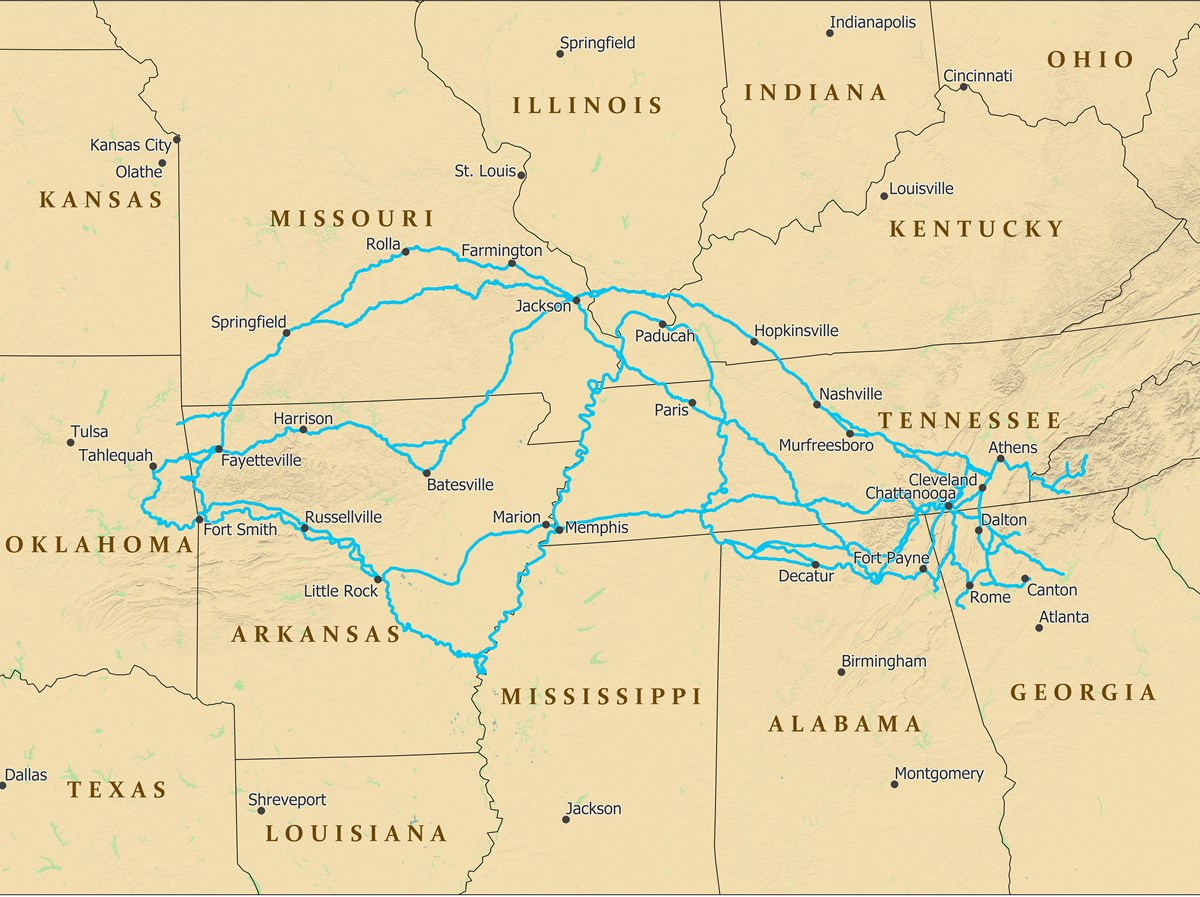

Trail of Tears

Alabama is not only the terminus of the Appalachian Trail, it has what some called "ends" of the Trail of Tears, for example, at Waterloo Landing.

In the article, Traveling the Trail of Tears in Alabama, Joe Cuhaj notes: "During the time of the Trail of Tears, Waterloo Landing, which is located in the town of Waterloo in the extreme northwest corner of Alabama, was situated on the banks of the Tennessee River. Since that time, the river was dammed to form Pickwick Lake, and the landing was flooded over. Because it was a final departure point for Indians from the South, Waterloo Landing was known as the "End of the Trail." Now, a historical marker denotes the location, and in September of each year a commemorative Pow-Wow is held here with traditional music and more."

Alabama has five "certified sites" that acknowledge the Trail of Tears.

|

| Cherokee Walking the Trail of Tears, by artist Sam Kitts. Source: NPS Trail of Tears Alabama |

A grim précis of the Trail of Tears, and the motives that drove it, is on the History Channel's Trail of Tears page.

In September 2020, PBS premiered a movie, DIGADOHI: Lands, Cherokee, and the Trail of Tears: