|

| Angela Davis mural, by Tim Kerr, Avondale neighborhood, Birmingham, Alabama. December 2020. |

In November I attended a dispute resolution workshop hosted by the Ohio State Journal on Dispute Resolution, which featured keynote speaker, Mariame Kabe.

Ms. Kabe and others in the workshop spoke a language new to me:

- Colonial erasure

- Abolition feminism

- Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) abolition

- Carceral state

After the workshop, I sought more information on abolition feminism ....

.... which led me to Angela Davis, who, until I visited the Avondale neighborhood recently, and saw her image on a mural, I had no idea was from Birmingham.

Sidebar: Or that the Girl Scouts had played a positive role in her life as an activist, oh, let's go ahead and say it - a revolutionary. An aside from this 2019 Washington Post article:

“[Angela Davis is] someone who, from a very young age, has provoked enormous controversy over whether her ideas were good or bad,” says Jane Kamensky, director of Harvard University’s Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America. “She cast herself as a revolutionary. And we have liked our civil rights activists firmly in the reform tradition, and we have liked our revolutionaries male.”

Abolition feminism

My current understanding of what it means to be feminist has expanded beyond my introduction in the 1970s and my membership in a Women's Political Caucus chapter in the 1990s. A sampling of new-to-me influences, learned since 2010, include:

1. Audre Lorde:

"I am a lesbian woman of Color whose children eat regularly because I work in a university. If their full bellies make me fail to recognize my commonality with a woman of Color whose children do not eat because she cannot find work, or who has no children because her insides are rotted from home abortions and sterilization; if I fail to recognize the lesbian who chooses not to have children, the woman who remains closeted because her homophobic community is her only life support, the woman who chooses silence instead of another death, the woman who is terrified lest my anger trigger the explosion of hers; if I fail to recognize them as other faces of myself, then I am contributing not only to each of their oppressions but also to my own, and the anger which stands between us then must be used for clarity and mutual empowerment, not for evasion by guilt or for further separation. I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own. And I am not free as long as one person of Color remains chained. Nor is anyone of you."

Source: Black Past

2. Women's Revolutionary Law of the EZLN in Chiapas, Mexico:

- "First, women have the right to participate in the revolutionary struggle in the place and at the level that their capacity and will dictates without any discrimination based on race, creed, color, or political affiliation.

- Second, women have the right to work and to receive a just salary.

- Third, women have the right to decide on the number of children they have and take care of.

- Fourth, women have the right to participate in community affairs and hold leadership positions if they are freely and democratically elected.

- Fifth, women have the right to primary care in terms of their health and nutrition.

- Sixth, women have the right to education.

- Seventh, women have the right to choose who they are with (i.e. choose their romantic/sexual partners) and should not be obligated to marry by force.

- Eighth, no woman should be beaten or physically mistreated by either family members or strangers. Rape and attempted rape should be severely punished.

- Ninth, women can hold leadership positions in the organization and hold military rank in the revolutionary armed forces.

- Ten, women have all the rights and obligations set out by the revolutionary laws and regulations."

3. Criticisms of the 2017 Women's March:

"The expanding dialogue about rape culture, and the indictments of patriarchy are inspiring, but they don’t change my ambivalence about organizing with White women, or my discomfort with the assumption that when White women organize for their freedom, they are organizing for mine too. They are not, and cannot, until they unpack the ways in which they have been taught to ignore the oppression of Black and Brown women – and continue to benefit from our oppression. Within hours of the March, some attendees Tweeted about how there were no arrests made that day at the major marches. Clearly, they lacked analysis or sensitivity for why peaceful protests where attendees are majority Black or Brown would be targeted for arrest.

"Fifty-four percent of White women voted for Trump. “Protecting” our borders and emboldening White supremacy were more important to them than autonomy over their own bodies and families."

Source: Katina Parker in A Charge to White Women

4. The 1950s Mine-Mill Strike in Grant County, New Mexico

OK. So what does holistic feminism have to do with PIC abolition?

From Angela Davis:

1. "When we look at women in prison, we learn about the system as a whole, the nature of punishment, the very apparatus of prison."

Source: Angela Davis in Windy City Times article by Yasmin Nair.

2. "Davis influentially condemned feminist approaches which emphasized incarcerating perpetuators, or carceral feminism. Instead she and other abolitionist feminists focused on how the state mirrored intimate partner violence and abuse as it punished survivors for self defense and forcibly sterilized hundreds of thousands of women."

Source: UCLA's Rebel Archives article, Angela Davis and Abolitionist Feminism.

3. "Confronting and abolishing the power relations embodied in PIC required a Black feminist approach that addressed the interwoven nature of state violence and people’s struggles.

"Davis’ Black feminist theory took shape in the everyday work of organizations like the Santa Cruz Women’s Prison Project and the California Coalition for Women Prisoners, which helped the voices and experiences of incarcerated women break through prison walls. Rejecting the machismo that characterized earlier prison struggles, women and their allies revealed the gendered violence and trauma both led marginalized women to prison and was exacerbated by state violence. As Californian prisons became infamously overcrowded, incarcerated people faced medical neglect and abuse even more extreme than the conditions described at Soledad years earlier. All these circumstances and the will of incarcerated women to struggle for their own survival built a new inside outside movement that continues to this day."

Source: UCLA's Rebel Archives, Introduction to series Sisters in Struggle: The California Coalition for Women Prisoners, Feminism, and Abolition.

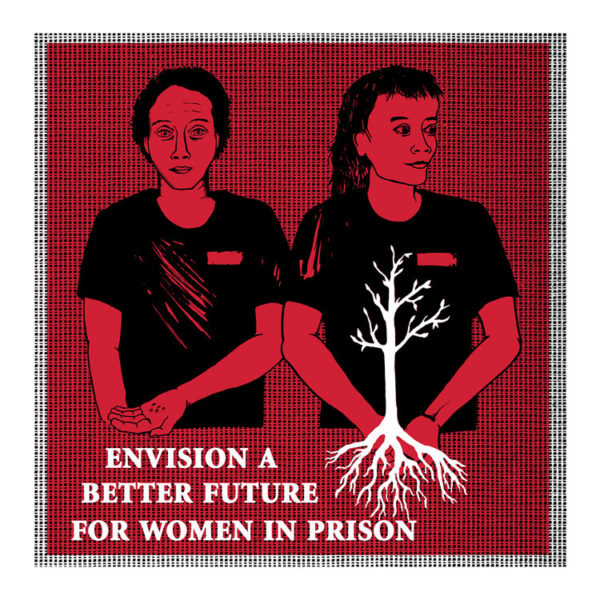

|

| Women in Prison, by Lydia Crumbley, 2009. Find it at Justseeds. |

I have so much to learn.

No comments:

Post a Comment